Sound

Clips Sound

Clips

Audio

– 'Spoonful' - Charley Patton (1929) Audio

– 'Spoonful' - Charley Patton (1929)

Audio

– For writer Francis Davis, Charley Patton was defined precisely

by his mysteriousness -- not that there aren't some interesting stories.

Audio

– For writer Francis Davis, Charley Patton was defined precisely

by his mysteriousness -- not that there aren't some interesting stories.

Audio

– Musican Honeyboy Edwards recalls that whiskey and dancing were

two crucial ingredients that flavored the blues

Audio

– Musican Honeyboy Edwards recalls that whiskey and dancing were

two crucial ingredients that flavored the blues

Audio

– Guitarist Corey Harris plays "Roki"

Audio

– Guitarist Corey Harris plays "Roki"

Audio

– For Honeyboy Edwards, learning how to ride freight trains helped

spread the blues

Audio

– For Honeyboy Edwards, learning how to ride freight trains helped

spread the blues

Listen

to Part 5 Listen

to Part 5

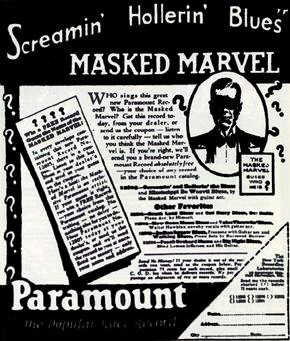

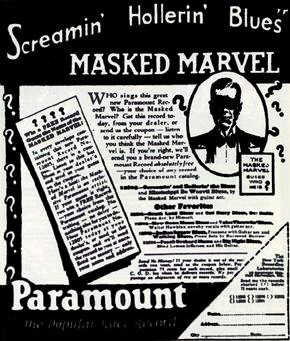

Photo:

Early Charley Patton (aka the Masked Marvel) promotional materials

Though musicologists can define

“the blues” narrowly in terms of chord structures and lyric strategies

originating in West Africa, audiences originally heard the music

in a far more general way: it was simply the music of the rural

south, notably the Mississippi Delta. Black and white musicians

shared the same repertoire and thought of themselves as “songsters”

rather than “blues musicians.” The notion of blues as a separate

genre arose during the black migration from the countryside to urban

areas in the l920’s and the simultaneous development of the recording

industry. “Blues” became a code word for a record designed

to sell to black listeners. Blues also came to be associated with migration

and wandering. It’s no accident that WC Handy’s tale of “discovering”

the blues takes place in a train station.

For transplanted blacks in

cities, blues was the music of home -- in the same way polkas were

the sound of the homeland for Polish immigrants. When blacks began to

migrate north the music traveled with them. Performers like Muddy

Waters began to use amplifiers and electric guitars, but the blues

always referred back to the rural south. Traditional styles could

be heard there until the late 1940’s when radio became the major

source of music. At the same time the songsters like Leadbelly were

putting their own stamp on the music.

But even as it sang of home,

it was embracing change — consorting with other musical styles,

and its Sunday sister Gospel. In Memphis, at the crossroads of the

rural south and the Mississippi River, the urban children of the blues

would take the music world under the names of rock and soul.

Today in isolated areas of

the south, traditional blues is still contemporary music. Ardent

acolytes have nurtured the flame with magazines and small record labels.

And in periodic revivals and enthusiastic festivals, fans around

the world can immerse themselves in that deep well of blues. In

spite of the disappearance of the “folk,” blues has survived to

become a sort of universal folk music

Humanities Themes:

· African influence on American music

· Migrations, urban dislocation, symbols of home

· Migrations – effect on the music and black culture

· The symbolic role of the train in blues music.

· How the recording industry popularized- and influenced-the

blues.

· The clear differences in first blues recording and all prior

recorded repertoire.

· The Myth of Robert Johnson: the larger-than-life-nature of

blues artists.

· WC Handy and the mythical origins of the blues

· Memphis and Chicago: how the mixing pot of cities transformed

the blues.

· Development of urban blues as step away from painful memory

even as it is embraced.

· Blues appeal to European and world audiences – elements

of universal (or ‘classical’) folk music.

Storyline:

Musicologists trace the origin

of the blues to West Africa. They define the music in terms of chord

and lyric structure. In a more general sense, it’s just the music

of the rural South. Its rise to popularity is, ironically, a by-product

of black migration to urban centers like Memphis in the early part

of the 20th century.

Like Bessie Smith, Ma Rainey,

and other popular black musicians, W C Handy performed in a variety

of styles, not just blues. He claimed to have “discovered” the blues

while waiting at a train station in Mississippi: the singer was

poor and rural, and the lyrics (which Handy found unintelligible at

first) referred to train routes. No doubt the story is apocryphal, but

it sets out the myth of the blues singer as a wandering minstrel

from the Mississippi delta.

The record industry, emboldened

by the success of a few black songsters, began to search out “the

real thing.” “Blind Lemon” Jefferson had no fixed address. Yet Paramount

Records took him from playing country picnics and house parties

and made him a star. Itinerant, disreputable and dangerous Charlie

Patton had flying fingers and a soulful style that made him a prototype

of the Delta bluesman. Huddie Ledbetter was almost as famous for

his life, which included time in penitentiary as for his music.

Robert Johnson, with his aura of mystery and demonic possession,

added the finishing touch to the archetype.

The audiences that consumed this music via

phonograph, radio, and jukebox were increasingly urban -- and increasingly

northern, as blacks began to migrate to cities like Chicago. Could the

blues continue to exist as “city” music?

Interview subjects:

Sam Charters,

veteran field recordist and author of “The Country Blues”

Corey Harris,

a young African American musician and folklorist who has studied music

in Mali, Cameroon, and the Mississippi Delta.

James Horton,

anthropologist, who can look at the sources of urban migration and patterns

of life and culture of the newly urbanized communities.

Robert McElvaine,

sociologist who can look at migration’s influence on music.

Kip Lornell, anthropologist

and folklorist, author of “The Life and Legends of Leadbelly”

and “The Musics of Multicultural America.”

Historic Recordings:

Examples of Traditional West

African music

Folkways Records (Smithsonian

Institution)

John & Alan Lomax recordings

of Southern field hand hollers

WC Handy’s “St. Louis Blues”

performed in a variety of styles

Blind Lemon Jefferson’s “That

Black Snake Moan”

Charley Patton’s “Pony Blues”

or “High Water Everywhere”

Robert Johnson’s “Cross Roads

Blues.”

Archival sound – Robert Johnson

session -- collection of Institute of Texan Cultures

|

Sound

Clips

Sound

Clips